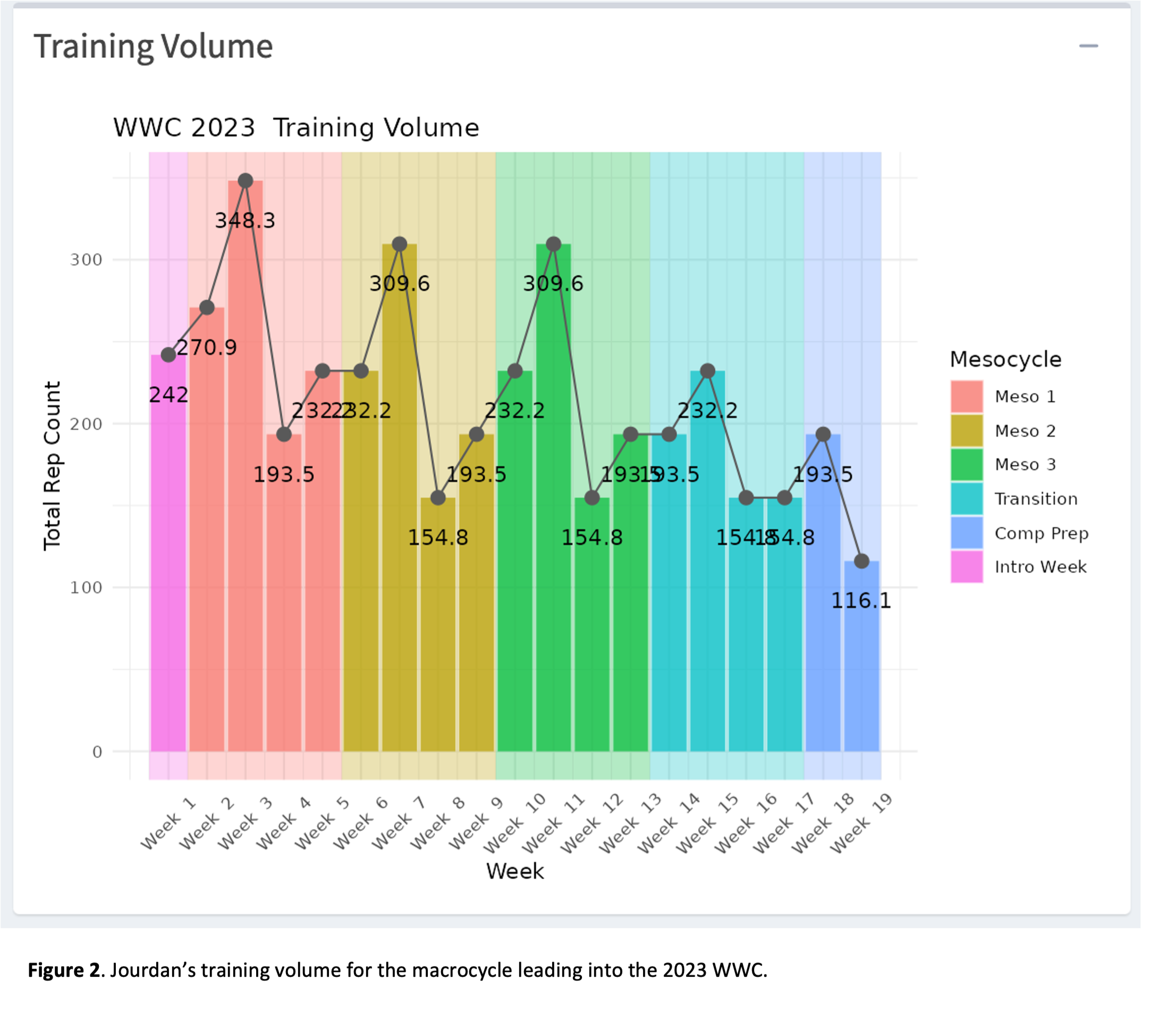

An adequate training plan in weightlifting commonly requires periods of training that will likely attenuate components of performance that are associated with sporting success. For instance, brief periods (~1-2 weeks) of training with an increased volume, commonly referred to as overreaching (1), are frequently used in Power & Grace training plans. This is often essential to allow athletes to maintain fitness throughout the training plan; consequently, training also induces fatigue, hence, a high-volume week is likely to decrease overall performance. Ultimately, however, we hope fatigue will dissipate at a greater than fitness, thereby allowing the athlete to hang onto some of the fitness gained and subsequently use this fitness to enhance performance (2). Figure 1 (4) displays this hypothetical fitness-fatigue paradigm (ignore the injury risk line since that does not pertain to this example). While a very common practice in weightlifting, intentionally decreasing performance later in a training plan may set off mental alarms! Sometimes for the coach and likely much more often for the athlete. Fortunately, at Power & Grace, we can collect data that can put our minds at ease!

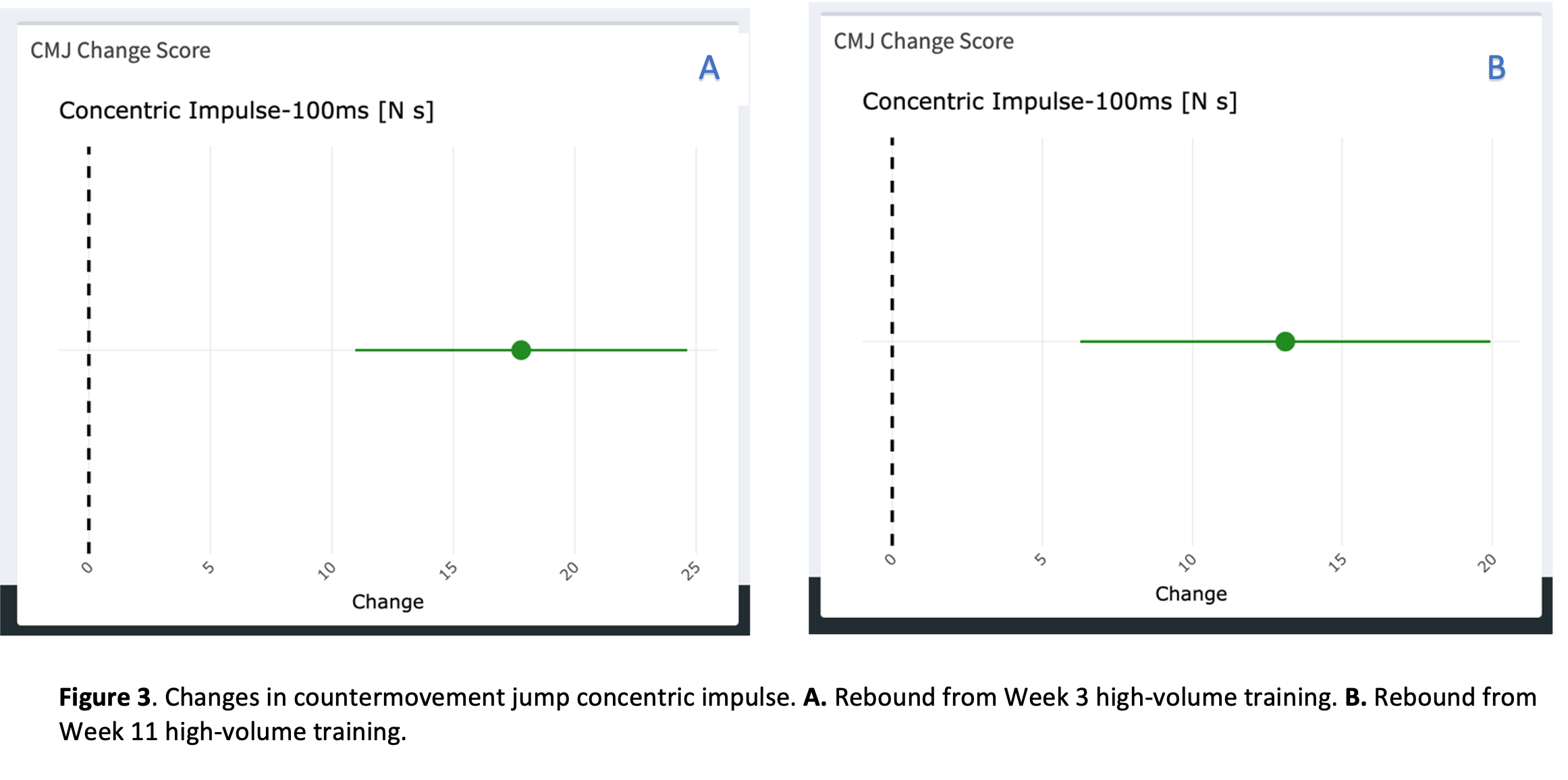

I have an excellent example of this scenario with a Power & Grace HQ athlete, Jourdan, as she prepared for the 2023 World Weightlifting Championships (WWC). Like all HQ lifters, we collect performance data on Jourdan to monitor fatigue and examine program efficacy. With the 2024 Paris Olympics around the corner, the 2023 WWC was a highly important competition for Olympic hopefuls. Put simply, this amplified the importance of communicating the data to Spencer throughout the training plan. The intriguing part of this story for me, however, is the involvement of Jourdan in these discussions. Jourdan was completing a squat workout using the velocity units we have at HQ, something Jourdan often uses when squatting. She came to me and asked how her jump numbers looked that morning. According to her, a) her squat numbers looked slow and b) her legs felt extremely fatigued. We examined her jump testing and sure enough, multiple jump metrics were well below normal for her. Looking at her weekly training volume (Figure 2) (number of reps completed across the competition lifts, squats, and pulls), this conversation took place at the end of Week 12 which was a very low volume week (155 reps). The week prior (Week 11) was a very high volume week (310 reps) that she said really took it out of her. What we were likely seeing is the residual effects of the high-volume week persisting through the low-volume week.

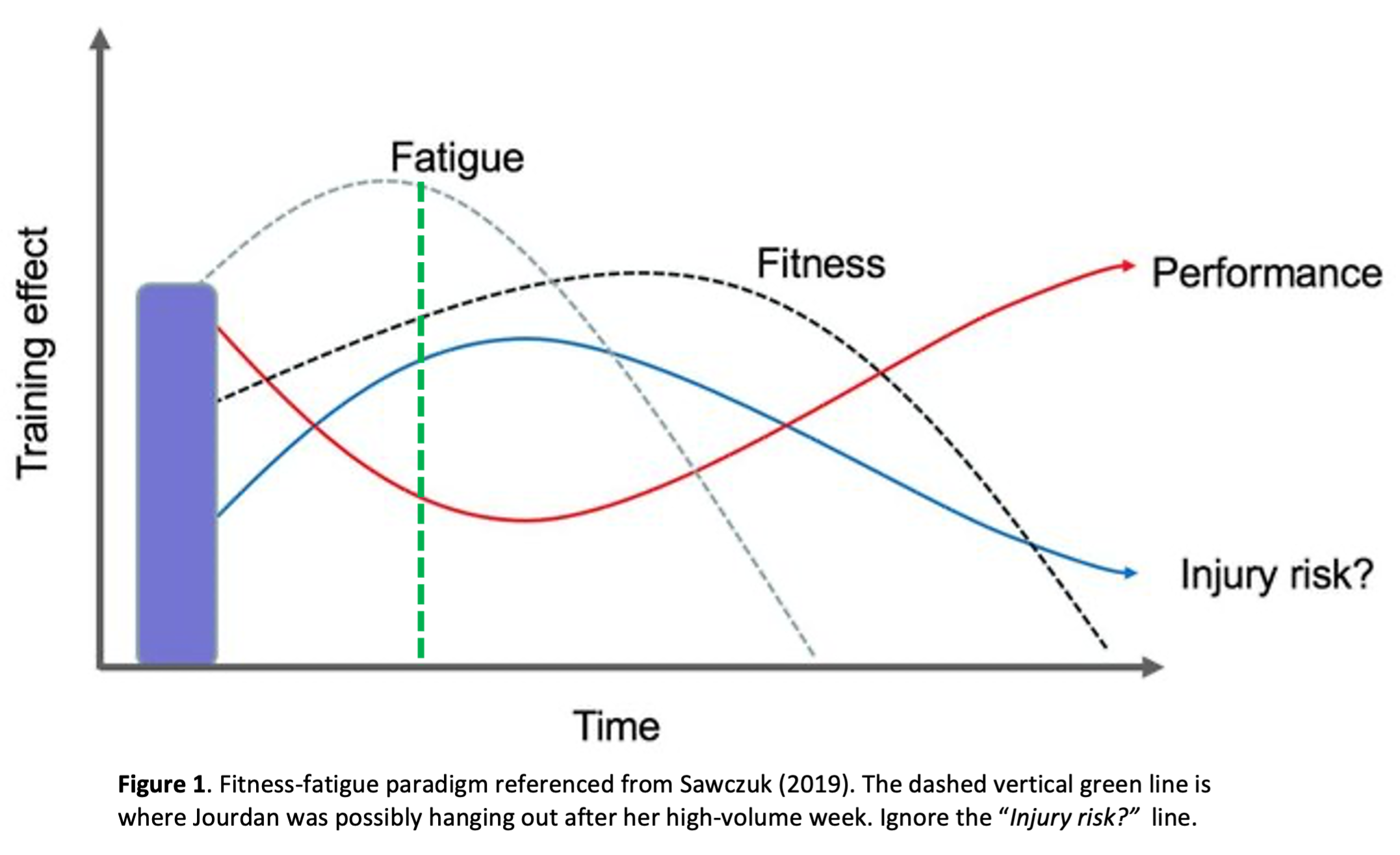

Following this discussion, I examined historical jump data from early in the training plan when Jourdan was dosed with high-volume training. Given spans of missing data in Mesocycle 2, I examined the data surrounding Week 3, the high-volume week in Mesocycle 1. Week 3 also resulted in jump performance decrements for Jourdan, however, her jump performance rebounded in the subsequent test session (Figure 3A; see an explanation of these plots in this previous blog). This is what Spencer expected to occur after the most recent high-volume week, nonetheless, doubt in program efficacy can creep into the coach’s mind when the athlete is in the trenches following a heavy dose of volume. Showing Spencer the historical data reassured him a dip in Jourdan’s neuromuscular performance should be expected and even welcomed as it is a byproduct of the high-volume week training (3) (see again fitness-fatigue paradigm, Figure 1). Additionally, discussing this with Jourdan allowed her to better understand her training plan and why she felt so fatigued two months prior to the competition (and that her suffering was not in vain).

Following this event, we can examine Jourdan’s subsequent jump performance to decide if she did indeed rebound from the high volume of Week 11. In the following test session, her jump metrics were improved back to normal (Figure 3B) as planned. Ultimately, the aim is to peak her neuromuscular system (partially assessed through jump testing) for competition, however, examining that is beyond the aim of this blog. We believe this to be a rather nice case example of how the data we collect can be an aid in coach-athlete discussions. Additionally, it is always interesting to take a glimpse at the intricacies that go into preparing a high-level athlete for a major competition. The takeaway from this should be a) purposeful data collection can attenuate coach and athlete stress and b) it is okay, and necessary, for all skill levels of athlete to periodically feel heavily fatigued throughout the training process!

- Bell, L., Ruddock, A., Maden-Wilkinson, T., and Rogerson, D. Overreaching and overtraining in strength sports and resistance training: A scoping review. J Sports Sci 38: 1897–1912, 2020.

- Cunanan, A.J., DeWeese, B.H., Wagle, J.P., Carroll, K.M., Sausaman, R., Hornsby, W.G., et al. The General Adaptation Syndrome: A Foundation for the Concept of Periodization. Sports Med 48: 787–797, 2018.

- Hornsby, W., Gentles, J., MacDonald, C., Mizuguchi, S., Ramsey, M., and Stone, M. Maximum strength, rate of force development, jump height, and peak power alterations in weightlifters across five months of training. Sports 5: 78, 2017.

- Sawczuk, T. Training loads and player wellness in youth sport: Implications for illness. 2019.